This essay by Sabrina Majeed first appeared in Offscreen Issue 11 (now sold out).

We have always been here.

Lurking in the shadows of your forums, passing silent judgment on your conversations, even joining in if we felt compelled to do so. You didn’t even realise it was us you were talking to, us you were so embroiled in heated debate with. We became good at disguising ourselves, donning ambiguous avatars and cryptic display names, basking in the freedom offered by anonymity. We congregated as our true selves in corners of the internet that you didn’t even know existed. Long before Pinterest and Tumblr became the designated spaces that you – you, with your anxious need to categorise and contain — would relegate us to. We were there.

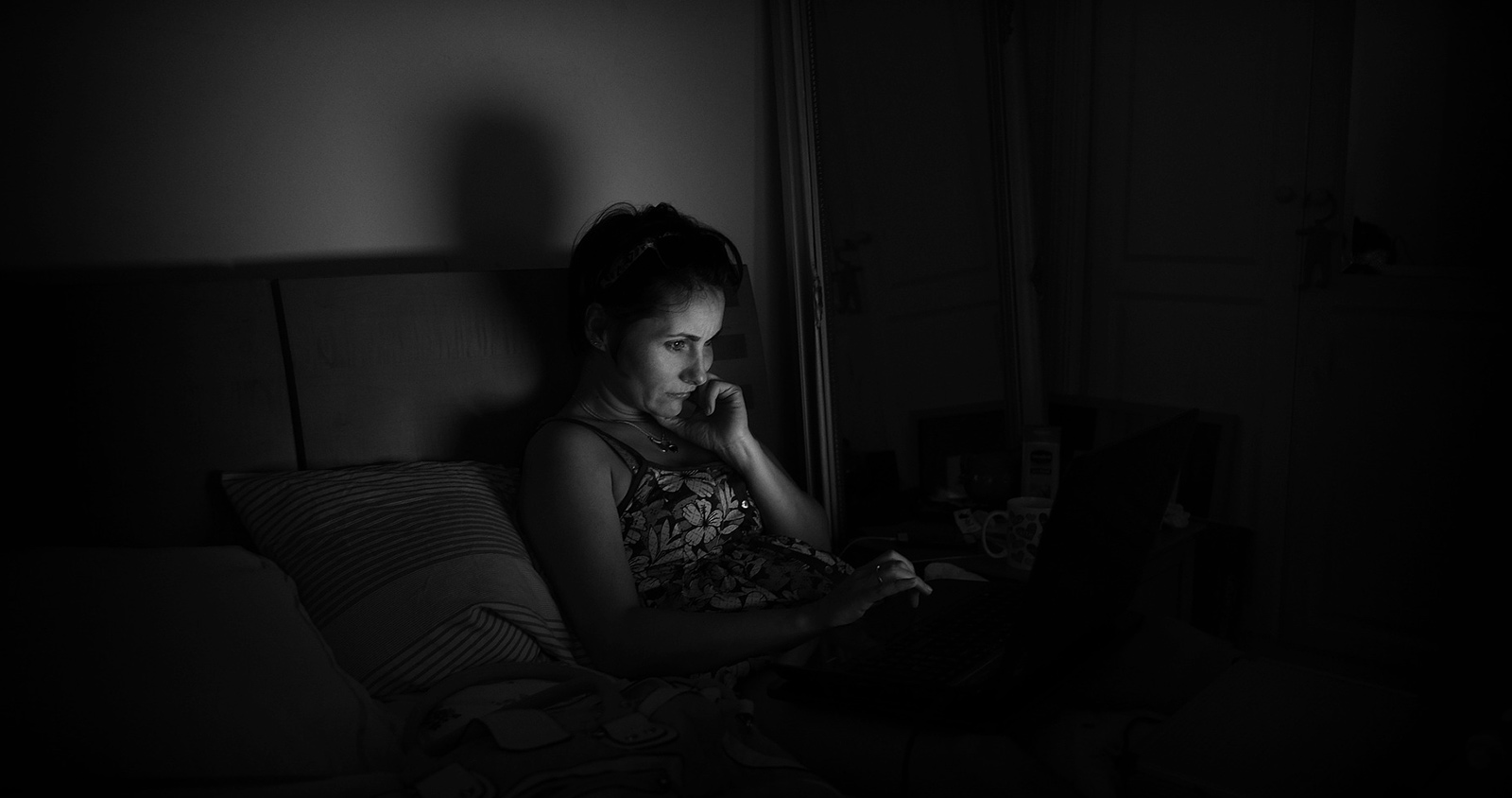

You didn’t really think you were the only ones who could spend hours in the solace of a dark room, illuminated only by the comforting glow of a screen, did you? Softly clacking away at a keyboard, leery of waking up a family who just couldn’t comprehend why you needed to be online at four in the morning.

For a young girl growing up online, the internet was a source of sexual awakening. There was the early solicitation for age, sex, and location, and the late-night instant messaging marathons with internet boyfriends. Whether I was perusing the female-dominated, libertine world of fan fiction, or curiously poking my head into a more visceral, male-oriented landscape, I always kept my pointer carefully positioned over an exonerating browser tab, ready to pull the trigger if I heard footsteps approaching my room.

The web does not discriminate in its seduction. Its siren call is a whisper of white noise with the resounding wail of a dial tone. It echoed in my ears when I was at school, at the mall, with friends, always beckoning, and insatiable in its demands for my time and attention.

Yes, we were there too! Furiously scrolling and clicking in an attempt to escape the banalities of adolescent life. But few noticed. We were erased. Just as we were erased from the pages of history, like our contributions to society and our participation in the wars that toppled dynasties and drew new lines in the sand.

Now you purport to ‘make room’ for us on an internet you’ve claimed as your territory, as if it hasn’t been just as much ours all along. The rise of social media holds us accountable to our true identities, and anonymity is no longer a guarantee. The threat of exploitation is all too common, and voicing one’s opinion in a public sphere always bears a certain amount of risk. We now have to fight to feel welcome in the very spaces we’ve always occupied. It’s retrograde.

Even those few sites where femininity is allowed to visibly flourish, the spaces that dare to cater to women’s interests are dismissed as frivolous and unsubstantial. Should those strongholds fall to their founders’ desperate need for male validation, then perhaps we will become digital nomads once more. In the past our attention was fleeting and we were loath to tie ourselves down, to nest. New plat- forms popped up like frontiers itching to be explored, and we happily planted our flag.

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell writes that Bill Gates had access to the early computers during his childhood and college years. Gladwell looks back on those early interactions with technology as foreshadowing for Gates’ later success. Twelve-year-old Mark Zuckerberg had ZuckNet, a messaging program built with Atari BASIC. It was arcade games for Elon Musk.

Where do I hear about the woman who found her calling after building custom Livejournal layouts, who learned HTML so she could spruce up her Neopets shop? Or about the designer who can trace her success back to posting desktop wallpaper art on DeviantArt and GaiaOnline?

We need to start talking about them. We need to understand and celebrate the origin stories of women in technology just as much as those of men, and make those stories part of our industry’s cultural lore. Not only for the sake of looking forward and inspiring the next generation of creators, but to be able to look back and be reminded that this is our domain too. We are experts, CEOs, and role models. You can’t make room for us, because we’ve always been here.

Enjoyed this essay? Support indie publishing and buy available issues of Offscreen for more thought-provoking reading material in beautiful print.