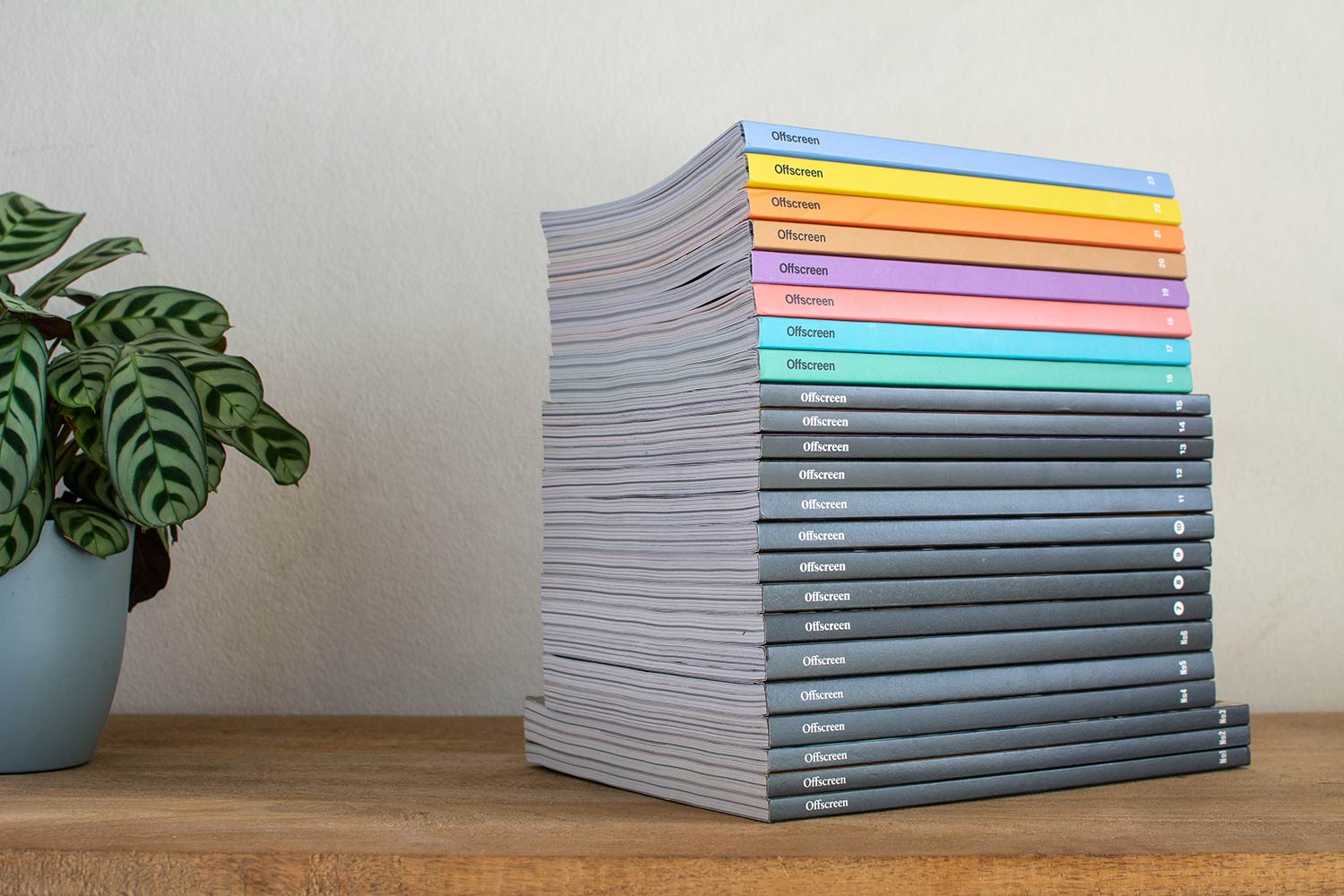

This essay by Molly Flatt first appeared in Offscreen Issue 20. You can buy a copy here.

Of the 185 books Bill Gates has recommended on his blog over the past eight years, only 12 are novels. During Mark Zuckerberg’s ‘year of books’ in 2015, when he crunched through twenty-three worthy tomes, works of fiction cropped up only three times.

I’ve made it something of a personal project to ask the tech people I meet in my day job to name-check authors they love. Peddlers of neuroscience, behavioural economics, and organisational theory feature highly. Peddlers of make-believe do not. When I ask them why they read so little fiction, their answer boils down to the same question: why would anyone waste time on made-up stuff when there’s so much real stuff to learn about the world?

Life is indeed stranger than fiction, as recent global events have proven all too well. It can feel indulgent, if not irresponsible, to spend my evenings romping through a novel about glass-blowers in fifteenth-century Venice when there are so many urgent present-day technological developments and political dilemmas to understand and have opinions on.

I think we can all agree that what the people creating new technology need more of right now is the ability to step into the shoes of others who don’t think, look, or live like them. I wonder what would happen if tech folk spent less time skimming trend reports and explainer journalism and more time truly trying to understand the perspectives of others. Might we finally see more diverse and nuanced products and platforms emerge?

Science tells us that this is one area in which make-believe can actually help. Several studies have proven the link between fiction and empathy. Probably the best known, conducted by psychologists David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano in 2013, found that reading literary fiction enhances the ability to detect and understand other people's emotions. ‘What great writers do is to turn you into the writer,’ Kidd explained. ‘In literary fiction, the incompleteness of the characters turns your mind to trying to understand the minds of others.’ Perhaps what we need to fill the empathy gap is imagination, not information.

In my own experience, fiction is also incredibly effective in helping people pay attention to the world. This may sound contradictory – after all, you’re not out there smelling roses if you’ve got your nose stuck in a book. But the best writers have a way of making you consider the mundane details of everyday existence with fresh eyes. And when you consider that many of our smartest startups have offered a new approach to prosaic things we used to take for granted (taxis, dinners, periods), you start to see how this sort of defamiliarisation might be the ultimate disruptor’s gift.

Of course, some of the techies I talk to do love novels. But their reading seems heavily, if not exclusively, skewed towards science fiction – just like every one of Gates’ and Zuck’s fiction picks. I’m also a massive fan of that genre. In fact, I’ve just published a novel set in London’s startup scene that has been described as ‘stealth sci-fi’, and a short story best explained as ‘near-future sleep-science meets Macbeth’. Many of our current technologies and ideologies were vividly predicted by writers such as George Orwell and William Gibson, and their works can indeed act as a potent gateway drug for lapsed fiction readers working in tech.

However, we all know that true creativity springs from unexpected connections. So if innovators really want to create something world-changing, they might want to aim for a more varied fictional diet. That fifteenth-century glass-blowing novel I mentioned? It’s teaching me deep lessons about the perennial preoccupations of Silicon Valley: hierarchy, belief, ethics, power. The best crime novels can offer a rigorous neural workout, exercising our brains’ pattern-recognition abilities. Even romantic beach reads can provide an insightful window onto a particular generation’s aspirations and anxieties.

Perhaps there’s a gender issue at play here too. Fiction is read by more women than men, and as we all know, in the tech industry, men predominate. But to dismiss novels, poems, and short stories as ‘sentimental’ or ‘irrational’ is surely to miss the point. Sentiment is the source code of humanity. Irrational instinct has more influence over our behaviour than cold hard logic. And fiction unscrews the circuit board of being, so if you want to hack the system, I reckon there’s no better place to start.

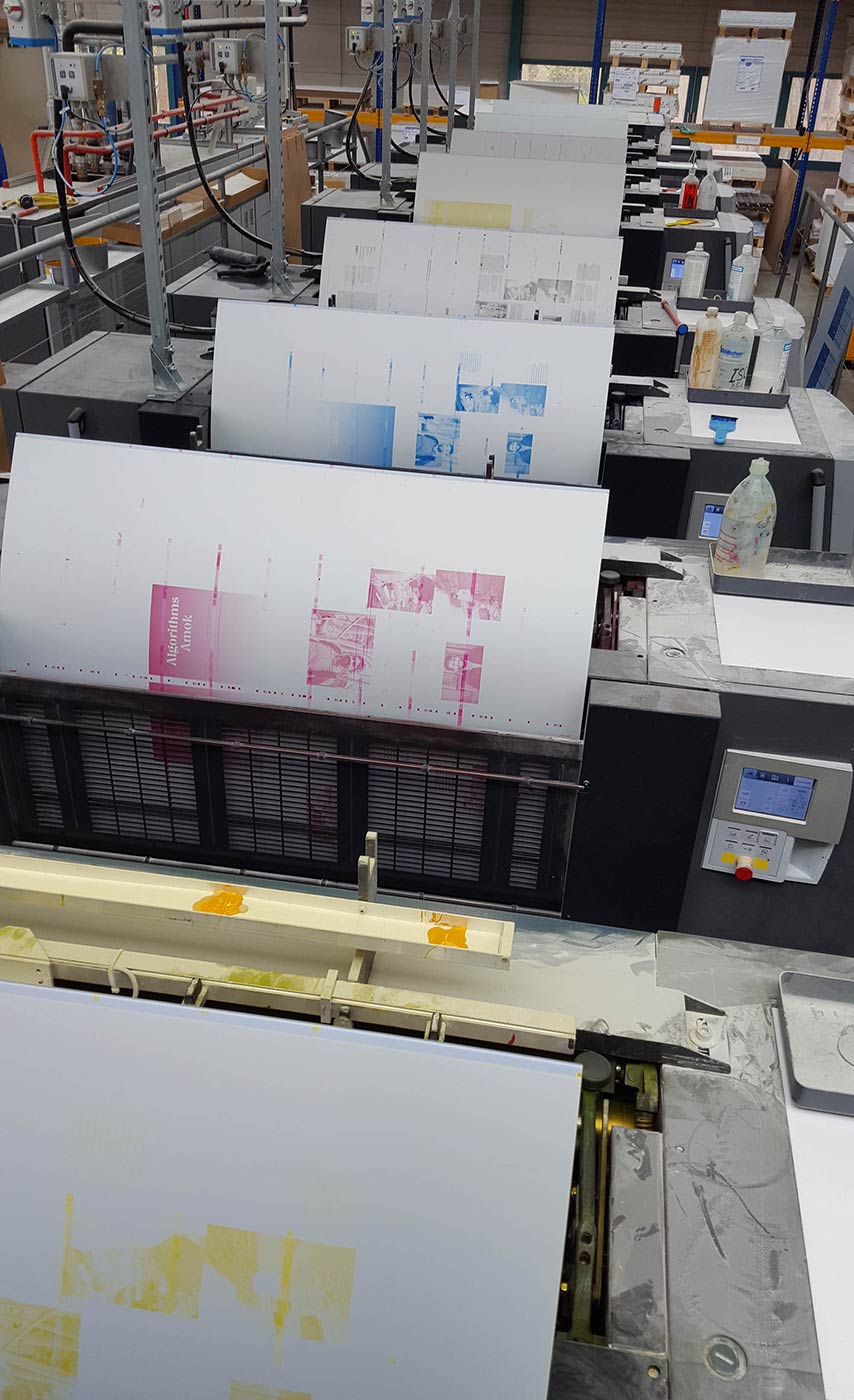

Enjoyed this essay? Support indie publishing and buy available issues of Offscreen for more thought-provoking reading material in beautiful print.